Methods of mapping

Desk research is a research that you do at your desk. Whether before you go out to the field, community or after you made some interviews and you would like to cross check what people told.

Observation is an act of noticing, perceiving, regarding attentively or watching for some purpose (to gain information). The point is that you keep yourself outside and don’t start to interact with the people, spaces, events you are observing. It sounds easy, but it can be challenging to stay in this neutral mode, not to react, not to interact. You can sharpen your observation skills while practicing meditation, where the main focus is to observe what we sense and see without judgement.

More information on that: here

Surveys/questionnaires are an easy format to spread in communities, especially nowadays with the available online tools that help us to create questionnaires and collect the answers as well. The practical tools are in our hands but still the mastery of creating the questions needs more explorations. How do we formulate the questions, what should come first and what after it?

You can read more on that topic here

Open talks can be a good tool for mapping as well. Sit down somewhere and start to talk to people. Even though ethically is more correct when we introduce ourselves and also introduce why we are interested in certain topics

Interviews are set of questions asked directly from the interviewee face-to-face or nowadays online. Interviews differ from questionnaires as they involve also social interaction. Researchers need training in how to do the interviews. Researchers can ask different types of questions which in turn generate different types of data. For example, closed questions provide people with a fixed set of responses, whereas open questions allow people to express what they think in their own words.

More information of the strength and limitations of interviews you can find here.

Photovoice is a process in which people – usually those with limited power due to poverty, language barriers, race, class, ethnicity, gender, culture, or other circumstances – use video and/or photo images to capture aspects of their environment and experiences and share them with others. The pictures can then be used to bring the realities of the photographers’ lives home to the public and policy makers or just to initiate discussion on the topic the pictures where taken of.

For a detailed description how you can carry out photovoice processes you can visit this website

Emotional or mental maps are a person’s point-of-view perception of their area, living enviornment or any other space. A mental map is a tool to get subjective interpretations of people about a certain territory.

You can read more here

Focus groups interview is a qualitative approach where a group of respondents are interviewed together, used to gain an in‐depth understanding of social issues. The method aims to obtain data from a selected group of individuals rather than from a statistically representative sample of a broader population. Focus groups allow to see the interaction between the members.

More information on that: here

Walking is a specific way of observing. We can just observe by walking but we can also make interviews while walking and see the interaction between the interviewees and the neighborhood. It can be also individual walks or even group walks.

You can find a scientific text about walking as a method for urban observation.

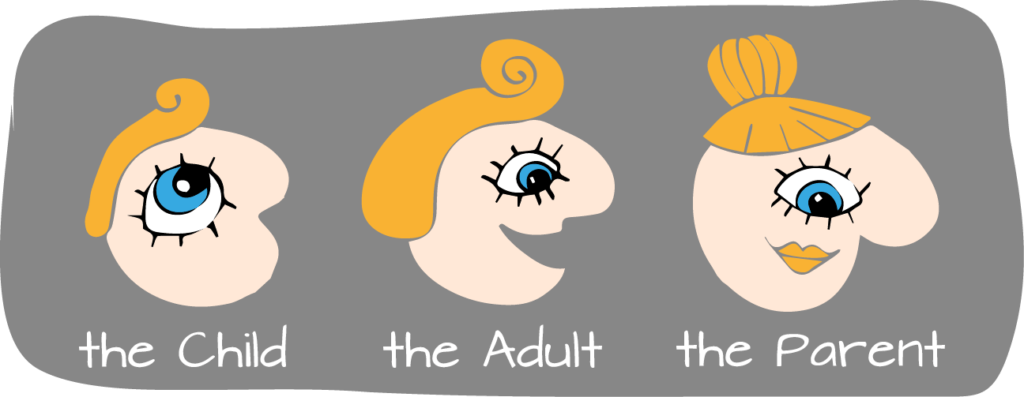

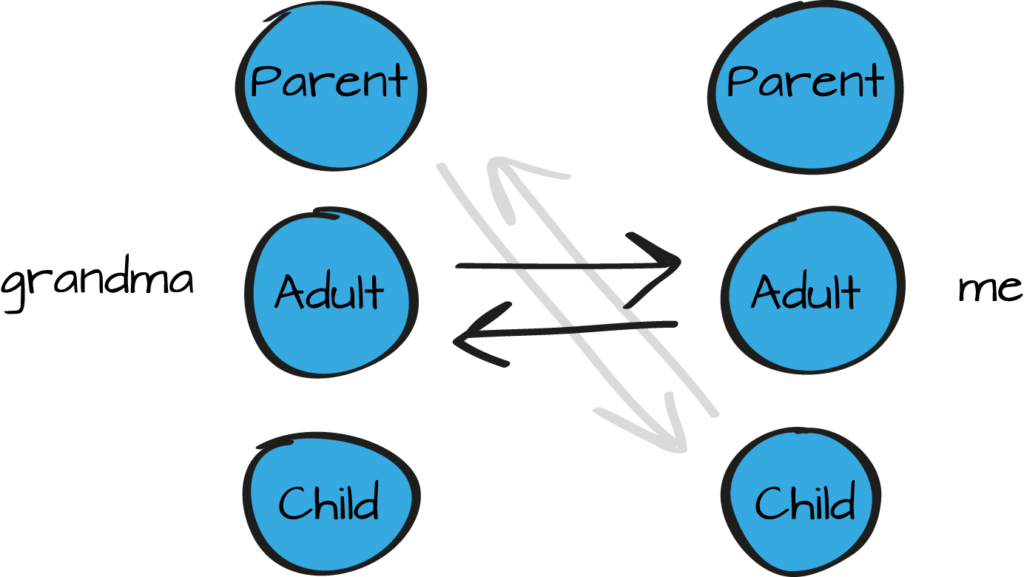

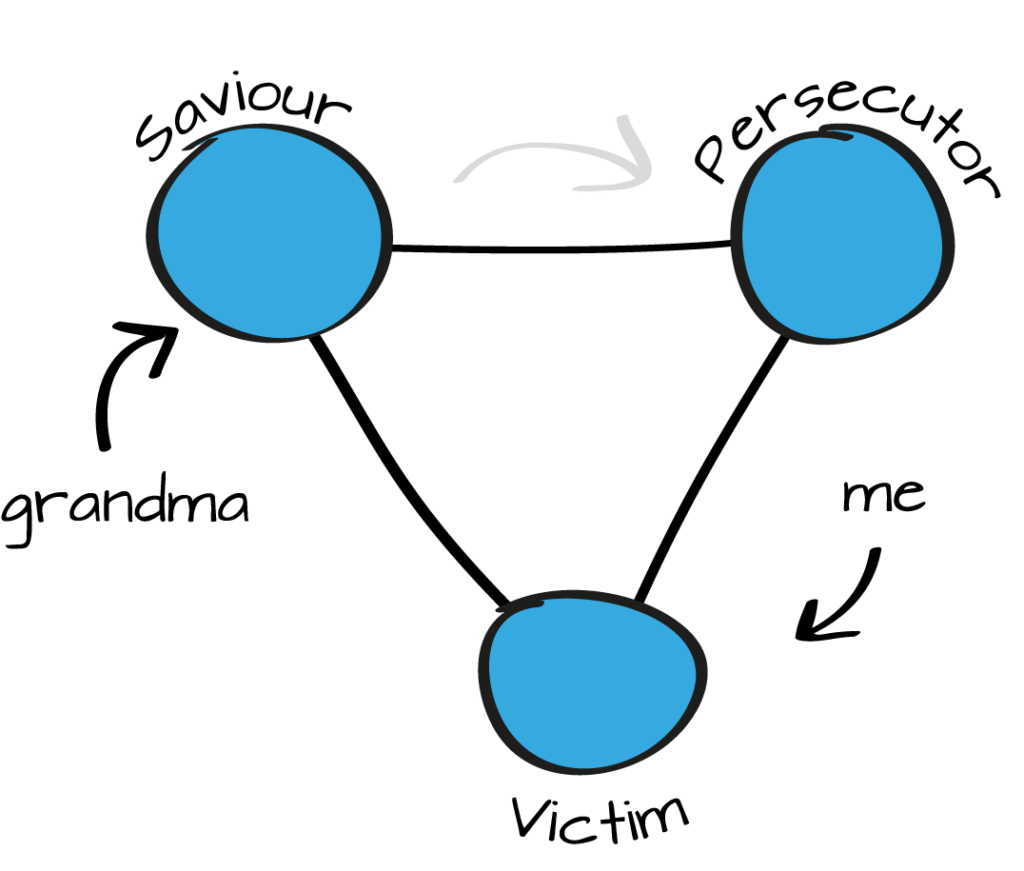

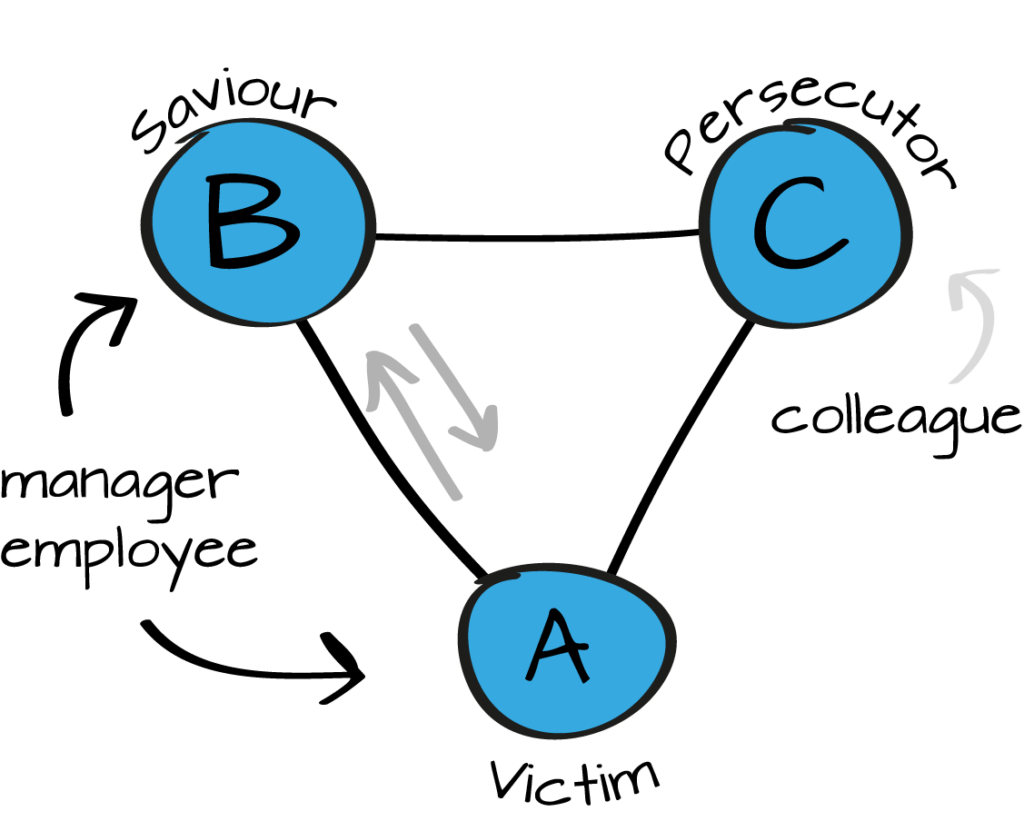

Although my colleague Martin is not my manager, he is a „senior“. I came to him playing the Child / Victim – the role that I learned when the glass broke at my grandma’s. Martin gave me the tools – factual information – needed to satisfy my needs. He reacted as an Adult and consciously avoided jumping into the role of the Savior. And by that, he changed something else as well: he disrupted the dynamics between the Child and the Parent and made me enter the Adult ego state.

Although my colleague Martin is not my manager, he is a „senior“. I came to him playing the Child / Victim – the role that I learned when the glass broke at my grandma’s. Martin gave me the tools – factual information – needed to satisfy my needs. He reacted as an Adult and consciously avoided jumping into the role of the Savior. And by that, he changed something else as well: he disrupted the dynamics between the Child and the Parent and made me enter the Adult ego state.